On This Day...March 3rd

Stirling Short Bomber in front of St. Paul’s cathedral on March 3rd as the start of a ‘Wings for Victory’ drive to raise money for aircraft.

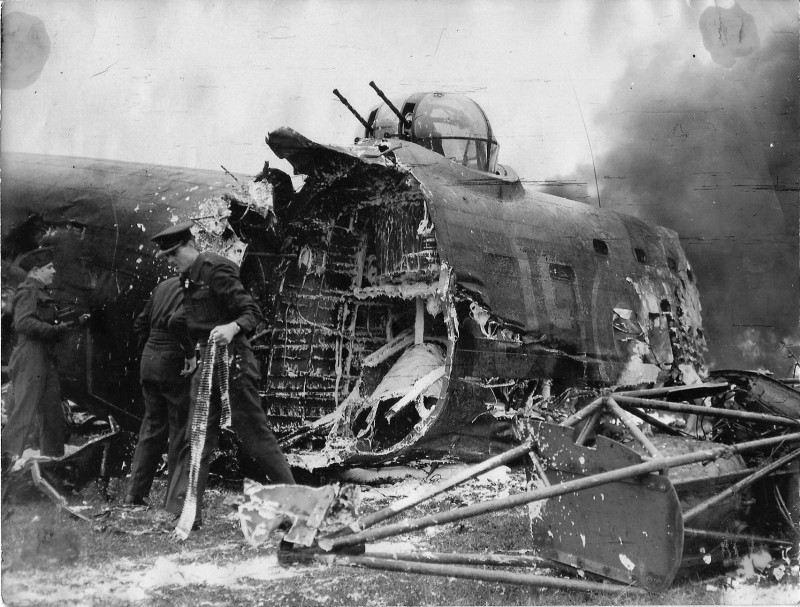

Avro Lancaster bomber suffers a ‘rough’ landing at RAF Fiskerton, March 3, 1945.

This photo of a StuG III assault gun by destroyed by US 4th Armour Division gives some idea of the catastrophic destructive power of armour piercing shells. March 3rd, 1945.

March 3, 1944 - Guadalcanal : Amphibious tank armed with two .50 caliber machine guns and a 37 mm gun.

- 5" Gun on the fantail off USS Gambier Bay (CVE-73), March 3, 1944.

General Douglas MacArthur hailed the Allied victory in the Bismarck Sea as, “one of the most complete and annihilating combats of all time.” The battle on March 2nd, 3rd, and 4th, stunned the Japanese military and shaped the course of the Pacific war. “Japan’s defeat there was unbelievable,” one of Vice Adm. Gunichi Mikawa (below), the commander of the Japanese Eighth Fleet at Rabaul, lamented shortly afterward, “It is certain that the success obtained by the American air force in this battle dealt a fatal blow to (the Japanese in) the South Pacific.”

The Battle of the Bismarck Sea was a game-changer, a cornerstone in modern air power history; a one sided naval defeat that involved not one single ship on the victorious side. The battle immediately convinced the Japanese that they could not operate even the strongest of escorted convoys in areas within range of land-based enemy aircraft.

With lessons learned and Allied strategy in place, the Japanese just couldn’t move their pieces on the board, and would essentially remain in defensive mode for the rest of the war.

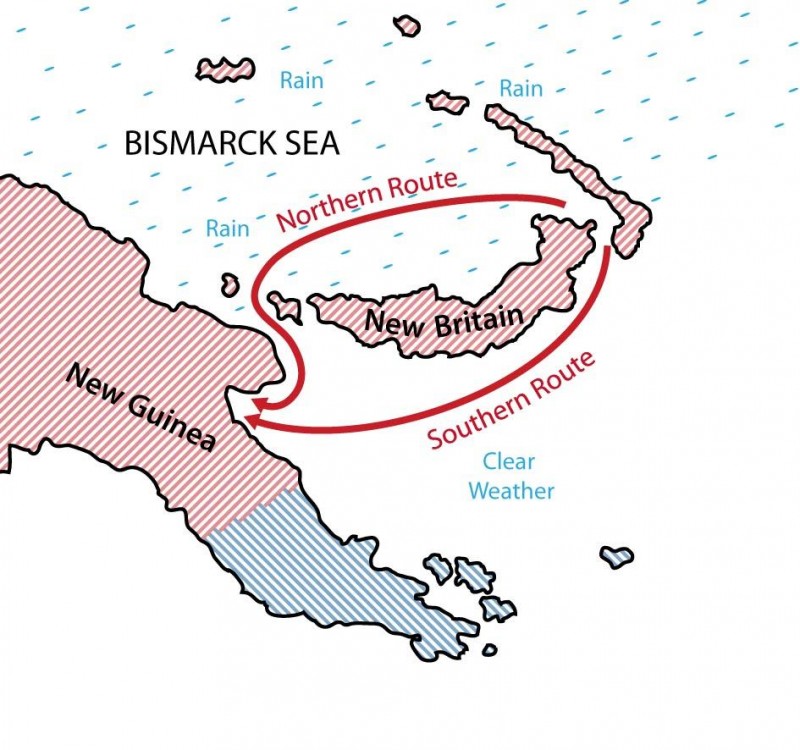

The Japanese had planned for the convoy to proceed to Lae along the south side of New Britain, as route they’d worked successfully before. But at the last minute the convoy was rerouted to the north of the island to take advantage of the cover offered by a storm front headed toward New Guinea. The weather was so bad on March first that reconnaissance planes could not locate the convoy for most of the day.

Early on March 2 a B-24 reconnaissance plane was able to navigate the clouds and relocate the convoy. Meanwhile, six Royal Australian Air Force A-20s from Port Moresby bombed the airfield at Lae from both medium and “tree-scraping” altitude and liberally strafed the runway and dispersal areas to mitigate any Japanese fighter protection, bombing aircraft in the open.

Less than two hours later, almost thirty heavy bombers hit the convoy. Still too distant for coordinated attacks by all types of aircraft, so the burden of the initial attack rested on the B-17s. The plan called for long-range P-38 Lightnings from the 9th Fighter Squadron to provide an escort, but the fighters failed to reach the rendezvous point on time, and the first wave of B-17s faced fierce enemy fighter attacks without protection. The low cloud deck and intermittent heavy thunderstorms contributed to the confusion. Eventually, the fighters would make it to the fight and repulse the Japanese Oscars, but not before nine of the B-17s were damaged.

B-17 pilots reported seeing the transport Kyokusei Maru breaking in half and sinking (her cargo hold containing a potent mix of ammunition and gasoline). Teiyo Maru, also suffered damage in the attack. In the afternoon, nine B-17s returned and dropped 1,000-pound bombs on the convoy, weather hampering the observation of the results.

Two destroyers, Asagumo and Yukikaze, picked up 820 survivors from Kyokusei Maru, left the convoy in the afternoon, and proceeded to Lae, where they arrived around midnight and unloaded cargo and personnel. The two ships rejoined the convoy the next morning.

In the morning of March 3, the convoy finally arrived within striking distance of the B-25 Mitchells and by 9:30 a.m. all the planes in the strike foce reached the assembly area, southeast of Lae, and were ready for action.

The first Allied planes roared overhead just as the commanding officer aboard Oigawa Maru, Captain Ino, was telling the troops assembled in formation on deck that they should not expect any air raids.

Allied air attacks were so closely timed and heavily concentrated that postmission intelligence reports judged it was impossible to ascertain which airplane or squadron actually sank each ship. B-17s flying at 7,000 feet dropped their bombs first, causing the Japanese vessels to maneuver violently and break up their formation, which effectively reduced their AA ‘sheild’. That left individual ships vulnerable to strafers and bombers. B-25s bombing from 3,000 to 6,000 feet also arrived overhead to drop their load of 500-pound bombs. Crew members reported seeing two burning Japanese ships ram each other while attempting to avoid the bombs. Much of the Japanese antiaircraft fire was focused on the medium-altitude bombers, which left an opening for bombers flying at minimum altitude.

Then thirteen Beaufighters swept in low on the water, strafing the whole length of the convoy. The Japanese destroyers (thinking the Beaus were torpedo bombers) turned toward the attacking planes to present a smaller target. This left the convoy with even less protection.

“We were indicating about 260 mph when we passed over the target,” Maj. John Henebry described in a postmission report of a broadside attack against one ship. “I fired in as close as I could as the decks were covered with troops and supplies. Just before I pulled up to clear the mast, my co-pilot released two of our three five-hundred pound bombs, one fell short and the other scored a direct hit into the side of the ship, at water line.”

The harrowing flying and devastating outcome of another run were described by 1st Lt. Roy Moore: “During this run I ‘cork-screwed’ the airplane by making undulating changes in altitude not varying from 50 to 100 feet, and at the same time skidded the airplane from one side to the other,” he recounted. “These evasive tactics were made to avoid any possible gun fire from the target. When in strafing range, I opened fire with my forward guns. The decks were covered with enemy troops. It is interesting to note that the troops were lined up facing the attacking plane with rifles in hand. However, the forward guns of the airplane outranged their small arms, as I saw hundreds of the troops fall and others go over the side before they could bring their guns to bear.”

Last in line were the A-20s, in groups of two or three aircraft, which increased their firepower. This massive volley of bullets had the effect of ending any deck gunfire.

The attack was perfectly timed, Allied planes arrived just after Japanese navy planes protecting the convoy had departed - but before their Japanese army aircraft replacements had arrived. Only twenty minutes after the attack started, the majority of ships in the convoy were sunk, sinking, or badly damaged.

That afternoon, Allied air power returned to finish the job. March 3 was a costly day for the Japanese.

Eight transports and three destroyers were at the bottom of the Bismarck Sea. The destroyer Tokitsukaze floated helplessly all night and sank at sundown on March 4. Only the destroyers Shikinami, Asagumo, Yukikaze, and Uranami managed to escape.

The Allies, in comparison, lost four aircraft: one B-17 and three P-38s. Thirteen American aircrewmen lost their lives: twelve in the four lost planes, plus a gunner on one of Ed Larner’s B-25s when battle damage caused it to collapse upon landing.

For the several days, American and Australian airmen returned to the sight of the battle, systematically prowling the seas in search of Japanese survivors. General Kenney ordered his aircrew to strafe Japanese lifeboats and rafts. He euphemistically called these missions “mopping up” operations. A March 20, 1943, a report recorded, “The slaughter continued till nightfall. If any survivors were permitted to slip by our strafing aircraft, they were a minimum of 30 miles from land, in water thickly infested by man-eating sharks.” Time after time, aircrew reported messages similar to the following: “Sighted, barge consisting of 200 survivors. Have finished attack. No survivors.”

Kenney later faced thinly veiled accusations of war crimes for this order.

A tactical report by 2d Lt. Charles Howe detailing his March 3 attack (in B-25-C1 No. 980) is typical: “Considerable time was spent after the release of all my bombs on strafing survivors and supplies which were strewn as far as the eye could see. On one strafing run against a previously damaged destroyer, I caught the survivors in the act of launching lifeboats. After firing for about seven seconds, I ceased firing to find the lifebloats overturned and the crowd of men attempting to gain the lifeboats definitely out of action.”

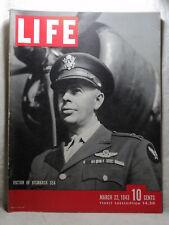

The public rejoiced after hearing media reports that Japan suffered fifteen thousand casualties at the Battle of the Bismarck Sea. The New York Times and other newspapers ran the story on their front pages, and Life magazine featured General Kenney on its cover.

The exact number of soldiers who perished and ships that were sunk aside, the Battle of the Bismarck Sea was a complete and decisive victory for Allied air power. Only 820 Japanese soldiers, in no state to fight, made it to Lae. Kenney’s congratulatory message to his staff summed up the effort well: “Air Power has written some important history in the past three days,” he wrote. “Tell the whole gang that I am so proud of them I am about to blow a fuze.”

Japanese media never mentioned the battle, but in a macabre footnote, two weeks later, Tokyo announced that in future all Japanese soldiers were to be taught to swim.

Excellent. It doesn't get much more interesting than this!

'Nuff said.

Thank you, Jeff. It’s hugely interesting reading about and researching these stories. Learning every day.

I'll bet!

David, You sure put a lot of effort into this, and its much appreciated, Thanks

Agreed !

Appreciated, Terry, especially considering your modeling interests.

Thanks for supporting the series.

Interesting as ever, David.

Cheers, @roofrat. Appreciated as ever.

The Battle of Bismark Sea in one word "Carnage" .

I've seen several of the low levels shots of the B-25's flying sweeps before. However, some of them are new and one is colorized. Total war...with out survivors ...ethnic cleansing. It gives pause for thought.

I’ve never read such a well documented one sided combat and the ensuing...what was the name, carnage? Sounds more like sheer atrocious war crimes. Anyway, there’s no doubt if the table was on the Japanese hand, they would have made exactly the same, one way or the other. That cockpit shot of the beau is priceless

It’s tough reading, Pedro. I do think the ‘no surrender’ policy of the Japanese did make the Allies dehumanise the enemy. At times, in the likes of Iwo Jima and Tarawa I’ve posted verbatim accounts of soldiers who described “extermination” rather than war. In this theatre there really was no quarter, it was very much kill or be killed.

David, @dirtylittlefokker

This is another story that brings it home... The horrible costs of War.

Our family had another member who was a B-25 pilot and flew in the Pacific. His name was 2nd Lt. Thomas V. Smith, and he was my Dad's cousin.

He flew with the 100th Bombardment Squadron, 42nd Bomb Group. He was killed in a flying accident over the Sulu Sea near Palawan, in the Philippines, on April 8th, 1945.

His body and those of the rest of his crew were never found... Thomas V Smith is memorialized at Tablets of the Missing Manila American Cemetery Manila, Philippines

Our family had a tombstone placed for him in the family cemetery. Here's his head stone.

I found a good picture of some planes from this unit several years ago. His unit was called the "Crusaders".

This is how the events leading to his death were recorded by one member from his unit...

On the 8th some more boys went down. Our C.O. and his crew were on a flight to Leyte with another plane when decided to do split S’s. He peeled off and into his routine, as he called his wing on the radio. He said “Peel off and follow me”, and seconds later he disappeared into a cloud. The second ship followed. The second ship broke out of the cloud just in time to see a huge splash in the ocean below. Circling, they saw a bunch of debris; Mae West’s and scrap covering the water. That is all.

Here's the "un official" version...

On a routine training flight to Leyte on 08 April 1945, B-25 #43-36015, piloted by the 100th Bombardment Squadron commander, crashed in the water while practicing operational maneuvers. The deaths of the crew of six men were listed as accidental. The members of the crew were as follows:

Capt. Robert D. Smith, Squadron Commander

2nd Lt. Robbie Peel

2nd Lt. Thomas V. Smith

2nd Lt. Joseph L. Johnson, Jr.

Sgt. James E. Levin

Cpl. Wynn W. Daily

I'll get a copy of the MACR report and hopefully know more about the events.

His unit was well versed in attacking Japanese shipping. There are a lot of ways to die during a War, or even peace time for that matter...

David, the Battle of the Bismarck Sea is really one of my "favorite" battles, because it was truly another turning point and the margin of victory was so significant. It had ramifications for the Pacific war in air, at sea, and on land. But the grimness of the affair is instructive for me: One account from a Beaufighter pilot that I read describes a strafing run on one of those ships that had turned towards the approaching aircraft, thinking to present a smaller target for torpedoes, only to have unwittingly proffered the troops crowding the decks as the perfect target for the murderous fire of the Beaufighters' guns. The pilot wondered what the "sticks" were, flying up into the air like that? Was he shredding the lumber of the decks so severely with his gunfire? But no, he realized, those were human body parts...

As Tolkien's Faramir notes, we do not delight in the sword for its bright swiftness, nor puissance in battle for its own sake, but only for the love of that which they defend.

Fascinating David. First, the Lanc. If they all walked away, then “rough” was an acceptable landing.

In hindsight, strafing survivors seems atrocious, and likely was. But as you noted to Pedro, the mindset of the Japanese leadership and most of the military was to fight to the death. Atrocities happened in the ETO, but they were rare compared to what the Allies had to face in the PTO. It’s hard to say what any of us would have done if we were present back then.