John Bridgers’ account of the loss of USS Yorktown

June 4, 1942: in addition to the US fliers sinking three Japanese carriers in the morning, the aircraft of the surviving fourth carrier, Hiryu, hit USS Yorktown; after survivingtwo strikes, the majority of the crew was evacuated. Yorktown survived another day, until she was torpedoed by the submarine I-168.

Among those aboard was Ensign John D. Bridgers, who would survive, go aboard USS Saratoga for the Guadalcanal invasion, and end up on Guadalcanal after Saratoga was torpedoed after the Battle of Eastern Solomons. He would eventually arrive in Bombing-15 of Air Group 15, the top-scoring Naval air group of the war, and on October 25, 1944, as a 24-year old Lieutenant Commander and Executive Officer of VB-15, he led the entire 480 plane strike from nine carriers of Task Force 58, a mission in which he bombed and helped sink Zuikaku, the last survivor of the six Japanese carriers that attacked Pearl Harbor.

Here's his account of Midway (from my book, "Fabled Fifteen: The Pacific War Saga of Carrier Air Group 15"):

At the end of May, John Bridgers reported to Bombing 5 aboard the USS Yorktown, which had just returned from the Battle of the Coral Sea with major battle damage. The U.S. Navy knew that the Imperial Japanese Navy was headed for Midway Atoll to support an invasion, and the response was “all hands on deck.” When specialists completed the survey of damage to Yorktown, they reported to Admiral Chester Nimitz, commander-in-chief of the Pacific Fleet, that it would take at least ninety days of all-out effort to repair the ship. Nimitz's response was that they had three days. When Yorktown put to sea, repair crews were still aboard hard at work. As Bridgers remembered, “One repair was a large metal plate covering a hole in our Bombing 5 ready room, through which a bomb had penetrated to the lower decks during the Coral Sea Battle.” Yorktown sortied from Pearl Harbor on June 1, 1942, headed for Midway.

Bridgers only saw limited action in the most important battle of the Pacific War. “My first operational sortie from a carrier at sea, other than my brief qualification flight from the Enterprise, was a 150-mile two-plane search flight from the Yorktown. As fate would have it, this was also my only active contribution to what became the Battle of Midway. What I remember the most about that particular mission was that the thin parachute cushion on which I was sitting caused me inordinate discomfort during that four-hour flight, a good part of which we spent circling the ships waiting to come back aboard. I was hurting so much that I thought little about my pending second carrier landing in an SBD. I just wanted to be able to stand up and ease the pain in the seat of my pants.”

On June 4, Bridgers was among a group of SBD crews held back for a second strike. As a result, he had a ringside seat for the fight to save Yorktown following the strike from the carrier Hiryu after the Americans found the Japanese at their single most vulnerable moment and sank the carriers Akagi, Kaga, and Soryu.

“The planes from the fourth Japanese carrier found the Yorktown before we found their ship and, in short order, we were under attack. We pilots of Bombing 5 had no duties other than to sit in our ready room. Unable to see out, we became more and more tense with no activities to release the tension. This was by far the toughest experience I had during the war. Our antiaircraft guns began shaking the ship, and we figured enemy planes were closing in. In steel ships, there were many plates to rattle and reverberate, so the firing of guns was a noisy din indeed. Most of us gathered around the plate patching the ready room deck after one fellow said, ‘Surely lightning won't strike twice in the same place!' The response was ‘But do you think the Japs know that?' Just as quickly, we dispersed to our empty desk-seats, and in short order the ship was struck by a couple of bombs. Since the overhead of our ready room was the underside of the flight deck above, we felt considerable jolts and the lights blinked out, to be automatically replaced by the dim red glare of battle lamps, and smoke was immediately evident. The attack passed quickly. In a few minutes, we were released to move topside and survey the damage. By now, our ship was dead in the water.”

Once on the flight deck, Bridgers was confronted with the cost of war when he saw bodies covered with tarpaulins. Yorktown weathered the first strike and was able get underway and bring planes aboard soon after, but then came a warning of a second strike inbound. “After the first attack, I observed that many had been injured because they were standing around upright and were either hit by flying debris or knocked up against projecting fittings. This must have been something noticed by the others, for all of us immediately lay down prone on the deck — a precaution well worthwhile. Next, there was a tremendous explosion and I was lifted bodily what felt like to be a foot or more off the deck. I now knew what a torpedo hit felt like. Almost immediately, it was evident that the ship was listing to one side and was once again dead in the water. Word was passed to abandon ship. I went back to the ready room and put on my Mae West life jacket. Back topside, knotted life lines had been let down over the low side of the hull and people were beginning to lower themselves into the water. Large life rafts were thrown over the side and the grim business got underway. I walked around the island and across the deck, trying to decide when I would go, secretly hoping someone would change their mind about the whole affair. I passed Captain Buckmaster taking a turn around the deck and he told me to hurry and get off the vessel. In several minutes, I passed him again and he said: ‘Son, I thought I told you get off this ship. Now get moving!'”

Once in the water, Bridgers encountered a wounded sailor whom he took under tow. After what seemed a long time, he and the wounded sailor were picked up by the destroyer USS Hughes.

Bridgers and other survivors were transferred to the USS Fulton for return to Pearl Harbor, where his personal problems took a turn for the worse. “Months earlier, when I shipped out from Norfolk, my main suitcase had been left behind in the rush of getting on the train at night. In it were my copies of my orders and pay records. On first reaching Pearl Harbor, the paymaster refused to open a new pay record until he had some confirmation of my orders. I wrote the paymaster in Norfolk and a validated copy along with a reconstructed pay record was waiting for me aboard the Yorktown when we sailed for Midway. Unfortunately, these were lost along with my size 14-AA shoes. When we got back to Pearl Harbor after Midway, the paymaster again refused to issue me my back pay on just my say-so. It was another month before I was re-entered on the regular payroll, and it was several years later before I got the back pay I had missed.”

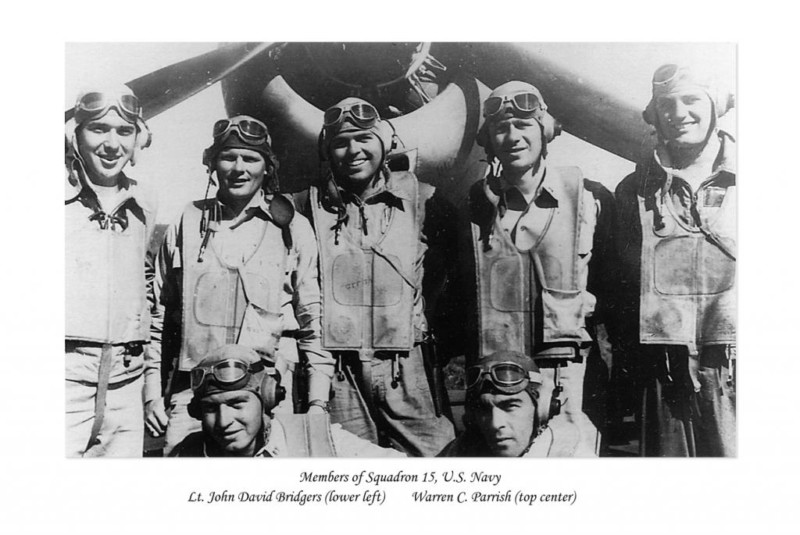

John Bridgers is left, bottom, in the photo here, with the men he commanded in "the Silent Second" division of Bombing 15 during 1944.

Great to see this account of the loss of the Yorktown Tom.

Poignant photo!

I see that battles with Navy officialdom can last almost as long as battles with the enemy!

Much longer.

Warren Street, who was John Bridger's childhood friend, died last December, the last member left of Bombing-15.

For a second there, I thought you were gonna post a build of an aircraft carrier (whew!)...I've never see ANYTHING built by you that didn't fly.

Very informative article Tom... There's nothing better than a first hand account.

Well done, Tom. Thanks for sharing.

For the record, his name was Warren Parrish (pictured in the center, standing). He was later Mayor of Aberdeen, MD where he lived next door to Cal Ripken Sr. and a young Cal Ripken Jr. I met him once at a pig pickin in Bath, NC years ago.