On This Day…April 23rd.

Posted a similar view of carriers at rest in Puget Sound; here are slightly different ships. USS Essex, USS Ticonderoga, USS Yorktown, USS Lexington, USS Bunker Hill, and and USS Bon Homme Richard at the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Washington, United States, 23 Apr 1948.

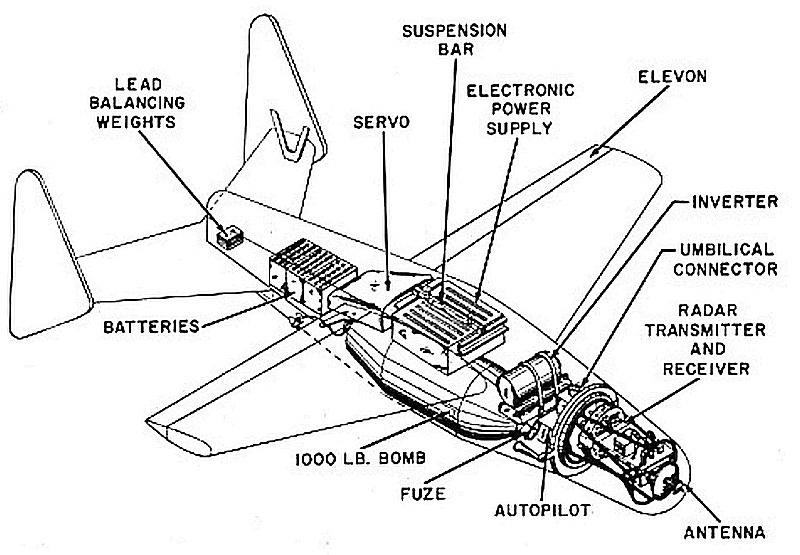

April 23rd, 1945 - Navy Patrol Bomber PB4Y Liberators deploy 'Bat' missiles against Japanese shipping off Borneo for the first time in combat - the only automatic homing missile to be used in World War II.

Several Japanese ships were sunk by 'Bats' and the Coastal Defense ship Aguni was almost destroyed from a range of 20 nautical miles (37 km). Several Bats were also fitted with modified radar systems and used to destroy Japanese-held bridges in Burma and other land-based targets. A total of 2,600 Bat missiles were deployed in WW2.

On 23rd of April 1944, U.S. Army Lieutenant, Carter Harman (of the 1st Air Commando Group) conducted the very first combat rescue by helicopter using a Sikorsky YR-4B in the South East Asia theater. Despite the problems set by high altitude, air humidity, and capacity for only a single passenger, Harman rescued a downed liaison aircraft pilot and his three British soldier passengers, two at a time.

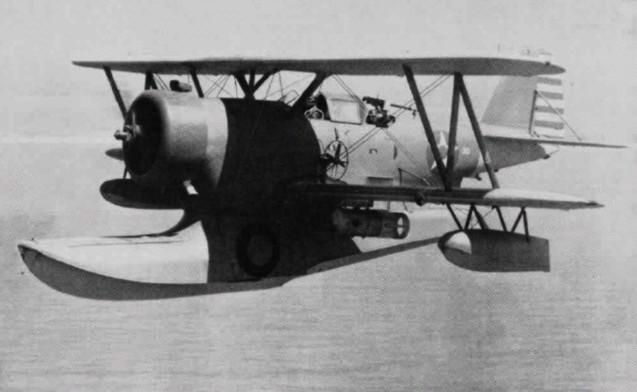

US Navy J2F-5 Duck aircraft in flight during anti-submarine patrol, 23 Apr 1942. Below is an example made by our very own Tom Bebout @tom-bebout - strangely enough in almost exactly the same position as the photo above.

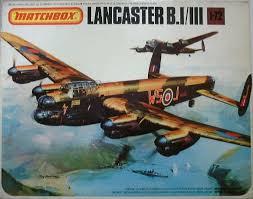

In the early hours of 23 April 1944, Sergeant C.H. Chandler of the famous 622 Squadron was taking part on a raid over Dusseldorf. His record of what happened after they dropped their payload is laid out below...

"We were a XV Squadron Lancaster III crew from Mildenhall on our 17th op and we were hit simultaneously by heavy flak and cannon fire from an Me 109 at the precise moment that our bombs were released on Dusseldorf. Being the flight engineer, I was standing on the right-hand side of the cockpit, as was usual during our bombing run, with my head in the blister to watch for any fighter attack that might occur from the starboard side."

(The 622 Squadron Lancaster LM477, GI-L, with its crew. Sgt C H Chandler far left)

"The bombs were actually dropping from the aircraft when there was a tremendous explosion. For a brief period of time everything seemed to happen in ultra-slow motion. The explosion knocked me on my back; I was aware of falling on to the floor of the aircraft, but it seemed an age before I actually made contact. I distinctly remember ‘bouncing’. Probably lots of flying clothing and Mae Wests broke my fall, but under normal circumstances one would not have been aware of ‘bouncing’.

"As I fell I ‘saw’, in my mind’s eye, very clearly indeed, a telegram boy cycling to my mother’s back door. He was whistling very cheerfully and handed her the telegram that informed her of my death. She was very calm and thanked the boy for delivering the message."

"As I laid there I saw a stream of sparks pass a few feet above the cockpit, from back to front and going up at a slight angle. This caused me some confusion. If the sparks were from a burning engine they were going the wrong way. It was some little time before I realised that the ‘sparks’ were in fact tracer shells from a fighter that I did not know was attacking us."

"The illusion that the tracer shells were going upwards was no doubt caused by the fact that our Lancaster was going into an uncontrolled, screaming dive, but because of the slow-motion effect that I was experiencing, I did not appreciate this fact. This whole episode had taken 2 or 3 seconds at most, then the slow-motion effect began to wear off, and I became aware of the screams of the bomb-aimer."

"After the aircraft went through violent evasive dives they threw off the fighter … and the order to prepare to ‘bale out’ was withdrawn after they discovered that most of the parachutes had been destroyed..."

"My task now was to check the aircraft for damage and casualties. My checks started at the front of the aircraft, in the bomb-aimer’s compartment. I am afraid to say that my sheltered life had not prepared me for the terrible sight that met my eyes. It was obvious that this area had caught the full blast of the flak, and Alan Gerrard had suffered the most appalling injuries. At least he would have died almost instantaneously."

"Suffice to say that I was sick. At this stage I risked using my torch to shine along the bomb bay to make sure that all our bombs were gone. My report simply was that the bomb-aimer had been killed and that all bombs had left the aircraft."

"Next stop was the cockpit. The pilot had really worked wonders in controlling the aircraft and successfully feathering the engine that had been on fire. Then on to the navigator’s department; on peering round the blackout screen I saw that Ken Pincott was busy working over his charts, but that Flight Lieutenant John Fabian DFC, the H2S operator (the Squadron navigation leader), appeared to be in shock. However, once I established that there appeared to be no serious damage, I moved on. The wireless operator’s position was empty because his task during the bombing run was to go to the rear of the aircraft and ensure that the photo flash left at the same time as the bombs. Next, down to the mid-upper turret, where Ron Wilson had re-occupied his position, albeit only temporarily. (Unknown to me, he had suffered a wound to his ear that, although not too serious, would keep him off flying for a few weeks.)"

"On reaching the next checkpoint I was again totally unprepared for the dreadful sight that confronted me. Our wireless operator, Flight Sergeant L. Barnes, had sustained, in my opinion, fatal chest injuries and had mercifully lost consciousness. It was found later that he had further very serious injuries to his lower body and legs. He died of his wounds before we reached England."

"From the rear turret I got a ‘thumbs up’ sign from ‘Whacker’ Mair, so I rightly concluded that he was OK. As well as having to report the death of our bomb-aimer, and the fatal injuries to the wireless operator, I had to report the complete failure of the hydraulic system. The pilot was already aware of the fact that we had lost our port inner engine through fire, and that our starboard outer was giving only partial power. The bomb doors were stuck in the open position, and the gun turrets had been rendered inoperative because of the hydraulic failure."

They had just enough fuel to make it back to England, gradually losing height all the way, only to discover that their undercarriage was stuck as they came in to land. The remaining crew survived the emergency landing.

Love the carriers at rest.

When I read stories like this one of the Lancaster crew I sometimes think of the hustle and scurrying on aircrafts in similar situations, but because they don’t make it we never have the opportunity to really know what was going on in their minds. Suffice it to say that I’m grateful that Sergeant Chandler was able to write about his experience.

And Tom’s Duck is a great example to use as a guide.

Thanks again for doing these David. They are a real treat to read.

My pleasure, literally. Well...literally, literally, I guess.

Totally with you on the crews’ thoughts and emotional states - it’s a treat (although always with some bitterness) to have access to that sort of chaos and carnage. And bravery.

With you also on Tom’s Duck - she is a beautiful example.

Stories like Sgt Chandler's are truly amazing. Thanks for that, David.

Thanks, Tom. As Gary said (above), the personal memories of these events are an important and rare insight into what it actually felt like to be in these otherwise unimaginable situations.

A sobering story indeed.[Sgt. Chandler]. The Sikorsky film is interesting.

The Sikorsky film is fascinating on several levels. Different days, indeed.

Very lovely that Sikorsky promo video...

Michael, the thing that strikes me more than anything about that Sikorsky video is the innocence of it all. In a generation who were living through D-Day and Okinawa, it’s hard to believe the naivety. It really took another generation in terms of civilian population (and exposure to information) to appreciate exactly what those men did.