“If I take the wings of the morning, and dwell in the uttermost parts of the sea” Charles Lindbergh and the Ryan NYP “Spirit of St. Louis”

Is it an exaggeration to say that hardly any aircraft silhouette is better known than that of the Ryan NYP "Spirit of St. Louis"? This is rivalled only by the fame of its pilot, Charles Lindbergh. His dazzling and peculiarly contradictory biography displays many of the qualities necessary to be permanently imprinted on the public consciousness. His very path to the spheres of global fame seems eminently suited to the American dream: the likeable country boy, someone who five years earlier could not even afford the $500 deposit for the final examination of his pilot's licence. triumphs in a daring enterprise at which the most famous pilots of the day failed!

A few words about Charles Lindbergh and his path to the Orteig Prize

Indeed, born in Little Falls, Minnesota in 1902, Charles Lindbergh came from, as they say, good stock and grew up on his parents' farm against a backdrop of a supportive home. With regard to Lindbergh's later political ambitions, it is interesting to note that his father, a trained lawyer, sat for a time as a Republican member of Congress.

By way of a private pilot's licence - the parents had finally advanced the twenty-year-old the 500 dollar deposit - and the purchase of his first own Curtiss "Jenny", the young Lindbergh came into contact with flying, which at that time was still very shirt-sleeved and sometimes hair-raisingly dangerous. Early on as a wingwalker and stunt parachutist, later as an aircraft owner with sightseeing flights, display flights and giving flying lessons, the young Lindbergh tried to keep his head above water financially. The period of this "barnstormer" flying came to an end when he enlisted for service in the US Air Corps in 1924. Two years (and two parachute jumps, each of which he narrowly survived) later, he joined the Robinson Aircraft Corporation as chief pilot, an up-and-coming start-up with a lucrative licence to fly mail between St Louis and Chicago. During the following period, in which Lindbergh's eminent aeronautical and navigational talent was honed and refined by long cross-country flights by day, by night, over inhospitable terrain and in almost all weather conditions, the idea must also have matured to take part in one of the most prestigious and well-known aeronautical challenges of those days: the Orteig Prize!

A year after the end of the World War, Raymond Orteig, a Frenchman living in the States, offered the remarkable sum of 25,000 dollars for the first non-stop flight from New York to Paris, a feat that at the time seemed beyond all feasibility. In 1926/27, however, an international community of pilots had emerged whose technical equipment and flying potential made the achievement of this goal more and more conceivable.

The stars of the aviation world of the time were competing - and they failed, if they tried, in dramatic fashion. The famous French World War II pilot René Fonck, for example, barely survived when his overloaded Sikorsky S-35 ended up in a sea of flames at the end of the runway after the landing gear broke. Charles Nungesser and Francois Coli, also well-known aviators and French national heroes, took off successfully in a Levasseur PL 8, but disappeared over the vastness of the Atlantic and were never seen again. Another well-known aviator and promising candidate had unbelievable luck shortly before Lindbergh's flight: during a final test flight, Richard E. Byrd's Fokker C.2, heavily loaded with fuel, overturned on landing - the three crew members were able to leave the wreckage, which fortunately had not caught fire. This incomplete list of attempts shows that Lindbergh's later success was still accompanied by a fascination that the press and the public have always succumbed to: the Orteig Prize had proved that it would require sacrifices and that the road to fame was fraught with mortal danger.

On the genesis of the Ryan NYP "Spirit of St. Louis

Fortunately, Charles Lindbergh had soon gained financially strong supporters who wanted to guarantee him 15,000 dollars in capital. This included the 2000 dollars that Lindbergh was able to contribute from his own savings. To Lindbergh's delight, he was entitled to decide for himself which aircraft would be purchased with this sum and how it would be equipped. With this arrangement, the businessmen behind Lindbergh had shown foresight, because unlike his competitors, Lindbergh was sure that a single-seat and, above all, single-engine aircraft would win the race. After briefly flirting with existing and adaptable models such as the Bellanca WB-2 or the Travel Air 5000 built by Clyde Cessna, Charles Lindbergh came to a decision that was to make history: he would have an optimally suited aircraft designed and built according to his own ideas at the then still quite unknown "Ryan Aeronautical Company" in San Diego!

The creation of the "Ryan NYP" (anyone who guesses what the three letters stand for may write to me ) is an amazing story in itself. Obviously, the chemistry between company boss B.F. Mahoney and Lindbergh was just as good as that between Ryan's young chief engineer Donald Hall and the future Atlantic flyer. According to the contract signed on 25 February 1927, Mahoney guaranteed that Ryan would design, manufacture and deliver the projected aircraft, equipped with all the necessary instruments and the Wright J-5 Whirlwind radial engine chosen by Hall and Lindbergh as the engine, for a maximum of 10,000 dollars within only 60 days. Lindbergh, who was already known as a shrewd businessman in his younger years, could be as satisfied as he was excited.

That an aircraft was actually ready for the first test flights sixty days later, which fulfilled Lindbergh's expectations and made the risky Atlantic crossing possible, was due not only to the close and good cooperation with Hall and Mahoney and the enthusiasm with which the entire Ryan team had dedicated itself to the task, but also to the fact that an existing design, the Ryan M-2, could be used as a suitable basis for the development of the Ryan NYP. The design of the tailplane, which had been taken over unchanged from the M-2, can serve as an illustration. Although this was too small for the significantly larger Atlantic crosser, resulting in poor stability around the lateral and vertical axes, it was accepted by Lindbergh on the grounds that the constant attention it required could help him stay awake.

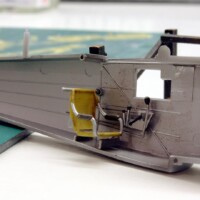

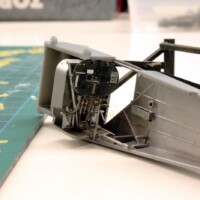

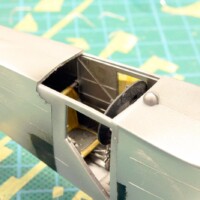

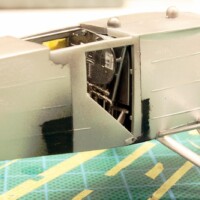

The positioning of the pilot in the middle of the fuselage without any direct forward view is astonishing. This allowed the installation of the large main fuel tank as well as the pilot's cabin within an aerodynamically extremely clean shape. Lindbergh and Hall paid the greatest attention to minimising air resistance and saving weight. This is also reflected in the instrumentation of the Ryan NYP: only the most necessary instruments were to be installed, so there was neither a fuel gauge nor a radio on board. Even the installation of a simple periscope, which could be extended into the air stream for a direct view in the direction of flight, the form of which had been developed by one of Ryan's technicians on his own initiative, did not initially meet with Lindbergh's approval.

The pilot's seat also testifies to the striving for efficiency and lightness: consciously and against all objections, Lindbergh insisted on the installation of an uncomfortable tubular chair: low weight, but above all the uncomfortableness was supposed to help him get across the Atlantic well and awake. Accurately the only concession to comfort that Lindbergh allowed himself to be persuaded to make in this context was to give him a frightening experience like from "Alice in Wonderland" during the 33-hour flight: In the middle of the Atlantic, already half deafened by sleep deprivation and the monotony of the engine roar, he felt himself growing larger and larger as if by magic, while the nearby fuselage roof was already threateningly pressing his head down. Startled out of this dream, he finally realised that the decreasing air pressure had inflated the air filling of the seat cushion. He had no choice but to pierce the inflated cushion with a knife to get back to normal.

Exactly sixty days had passed since the contract was signed, when on 27 February 1927 Lindbergh's Ryan NYP was ready for its first test flights. By this time, the handsome name "Spirit of St. Louis" had already been painted on the bow in honour of Lindbergh's backers.

With a length of 8.56m, a wingspan of 14.03m and a wing area of 29.64m2 with an empty mass of 964kg, it corresponded exactly to Lindbergh's ideas of a light, aerodynamically carefully worked out and reliable aircraft. Over 1.7 tons of fuel could be filled into the tanks, which would represent more than half of the maximum take-off weight of 2330kg.

Early in the morning of 20 May 1927, Charles Lindbergh sat in the cockpit of his Ryan NYP "Spirit of St. Louis", the tanks filled to the maximum, five sandwiches packed as provisions. According to optimistic forecasts, a short weather window over Roosevelt Field near New York would make take-off and flight possible, while a further postponement of the flight would play into the hands of competitors who were also waiting for the weather to improve. After a brief deliberation, Lindbergh gave the signal, the Wright J-5 Whirlwind took off- and would not come to rest until 33 hours and thirty minutes later on the other side of the Atlantic at Le Bourget Airport in Paris, to the attention of the world's press and the enthusiasm of the crowds gathered there. Charles Lindbergh had flown to worldwide notoriety and enduring fame.

Media hype and public attention would not let go of Charles Lindberg for the rest of his life. From then on, his further biography was marked both by the need to protect himself from the intrusive press and by the temptation to use his fame to formulate social and political concerns. In the context of this text, keywords will have to suffice; but for some readers they may still evoke associations even today. The arc spans from the tragic kidnapping and murder of the "Lindbergh baby" to his involvement in the right-wing "America First" movement and his falling out with F.D. Roosevelt, his trip to Nazi Germany and the subsequent appeals for strict isolationism on the part of the USA in the years leading up to the entry into the war, to the discovery of a whole host of biological descendants, only two of whom, however, had his wife as their mother.

On the kit and the building process

Revell's depiction of the Ryan NYP remains, oddly enough, one of the very few ways to build this icon of aviation history as a model. Fortunately, the kit from 2005 offers a good basis. However, there are a few things I have noticed that require correction or a little improvisation.

For example, the structures on the fuselage and the supporting structure, which are supposed to represent the framework of the fuselage construction that can be seen through the tension lines, are much too raised and angular. I sanded them flat and round, now I am much happier with the look.

Replace the three bent pipes of the tank ventilation on the central area of the fuselage roof. The kit moulds show strange "spigots", but they are far too short and too small (and would not survive the building process anyway.) Also replaced was the long pitot tube under the left wing, which was reproduced from a bit of plastic and wire.

A characteristic detail is also missing at the end of the fuselage: the linkages of the rudder and elevator were routed in large parts outside the fuselage fairing; I was able to supplement these missing cable pulls and rudder horns from etched parts and fine wire.

Once again I can praise Revell for the excellent quality of the decals. Especially the depiction of the ground metal planking at the front of the fuselage would have been difficult without the solution of depicting it with really well made decal material!

Finally:

I would have liked to use one of the two figures of Charles Lindbergh included by Revell! However, more energy has to be put into a revision of the disappointingly lovelessly made figures than success would have been worth to me. So I take this circumstance as a parable to the multicoloured biography of the Atlantic aviator: as mentioned at the beginning, Lindbergh's contradictory, versatile and thoroughly ambivalent figure is probably not so easy to capture in a single representation!

Thanks a lot for submitting this headline article, Roland @rosachsenhofer

A pleasure to read this informative article and a joy to look at your build of Lindbergh's aircraft.

Well done.

Thank you for this feedback and I'm glad you like the presentation!

Very good work, as usual Rolanmd @rosachsenhofer. The movie "the Spirit of St. Louis" is a very accurate adaptation of Linbergh's book by the same name.

Thanks Tom, I'm very pleased! An inspiring tip, I saw it once in my youth, I will watch this beautiful film again tonight - I am curious what impressions I will take away with me today!

A supreme build and a supreme article, Roland!

Congratulations!

Your words are motivation - thank you my friend!

Another “very well done” to you, Roland, an excellent article and model.

Thank you for your feedback , George!

"To say the most using the least" applies to engineering too. Great back story, informative and entertaining. A easy read that leads one into looking at what appears to be a simple stark model, but, with the story and photos, like a onion peals back the layers and shows a more complex build. Some great sharp, crisp photos with interesting back rounds as always Roland.

Thank you, for your time and efforts.

A beautifully pictorial comment - for which I gratefully say thank you!

Great build of a classic! Well done.

Thank you Greg!

A well done presentation - both the model and the history Lindberg's accomplishments and later eccentricities.

Thank you for your feedback! I'm glad you like the text too, thank you!

Nicely done all round. Looks great. the aircraft pictured is one of two surviving sisters to the original Spirit, they were an attempt to sell the design commercially, it was used in the movie, it is now on display at the Cradle of Aviation Museum on Long Island N.Y.

1 attached image. Click to enlarge.

Robert, thank you! That's interesting news, though, that I didn't know yet. Very welcome!

Very nice. Can I ask you what paint you used to represent the silver 'dope'?

Hi Kyle, thank you for your words!

The "Silver dope" was designed with Alclad metal tones, mainly "White Aluminum". I then determined the gloss level myself with Gunze acrylic clearcoats matt and gloss.