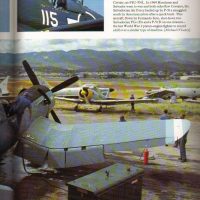

Fernando Soto's F4U-5NL (Hasegawa 1/48

Fernando Soto's Corsair, done back in 2003 with the Hasegawa 1/48 F4U-5N kit

A little-known fact of Corsair operations is that of the six air forces that flew the type operationally, two used their Corsairs against each other in the last air war in which Second World War fighters were first-line equipment.

The Corsair came to Central and South America in the late 1950s, when the U.S. military aid program supplied F4U-5Ns to the Argentine Navy, followed during the next five years by Corsairs provided to Honduran and Salvadoran Air Forces in Central America. While the Argentine Corsairs maintained their night-fighting capability throughout their service and flew from a carrier, the 10 F4U-5NL Corsairs provided to Honduras lost their night-fighting and winterized equipment before they left Litchfield Park, Arizona, in 1956. Honduras also received eight F4U-4 Corsairs in 1960-61, at which time El Salvador received twelve Goodyear FG-1A and FG-1D Corsairs.

In 1969, "The Soccer War" became the culmination of political and cultural differences between El Salvador and Honduras. While the name made good newspaper copy, it was completely inaccurate as to the cause of the war, which was actually the result of long-standing disputes regarding border territory between the two countries. Legend has it that this was the last combat appearance of the P-47 Thunderbolt; outside of some use of P-51 Mustangs flown by American mercenaries by the Salvadorans, however, all air combat took place between Corsairs of the two air forces.

The Honduran Air Force was alerted to possible hostilities with El Salvador on July 11, 1969. At this time, 13 of the 18 Corsairs originally supplied were still operational. Four F4U-4s were sent to San Pedro Sula on the north coast, while the eight remaining F4U-5s and one F4U-4 remained at Tegucigalpa.

In the early evening of July 14, while the Corsair pilots were at home packing for an extended trip to the northern combat zone, a Salvadoran C-47 converted to a "bomber" by cutting a hole in the lower fuselage through which 100-pound bombs were rolled out, attacked Tegucigalpa airport. Honduran pilots rushed back to their airplanes and several took off in pursuit of the long-gone C-47; nightfall brought them scurrying back since none of them had ever flown Corsairs after dark.

The next day two Salvadoran FG-1s and a P-51D attacked Tegucigalpa while the Hondurans were providing air support on the northern front. The unit commander went aloft in the one remaining F4U-5 but his guns were inoperable; a T-28A flown by Lt. Roberto Mendoza made a pass at one FG-1, hitting it with .30 caliber fire and forcing it to head north streaming smoke. While this was going on, the four Honduran F4U-4s struck the Salvadoran coffee port of Acajutla; using bombs and rockets they burned a small oil refinery but missed a major electrical plant. One of the Corsairs took a hit and force-landed in Guatemala, where it was interned for the duration of the conflict. On the following day, two of the F4U-4s intercepted 40 buses bringing Salvadoran forces to the front and shot them up.

Capt. Fernando Soto finally entered combat on July 17, when he took off from Tegucigalpa with two other F4U-5s flown by Captains Francisco Zepeda and Edgardo Acosta. With 400 hours in Corsairs since 1959, Soto was one of the more experienced Honduran fighter pilots. (Consider that this is an average of 40 hours per year, less than an hour a week; it is commonly considered in the U.S. that a warbird pilot who cannot average 2 hours per week in a high-performance aircraft is not "current" in the type.)

Soto's flight was for ground support. When they made their first pass, Zepeda's guns jammed and Soto ordered him to pull up and wait for rendezvous. During their second pass, Zepeda called that he was under attack from two P-51s. Soto pulled off his run and headed for the rescue. In his first pass at the two Salvadoran Mustangs, they broke in opposite directions; Soto followed the one that turned right and pulled inside the Mustang's turn. He fired three bursts of 20mm, and blew the left wing off the Mustang, which crashed before the pilot could bail out.

Later the same day, Soto and Acosta flew a mission to San Miguel in El Salvador. He spotted two Corsairs approaching from the north and jettisoned his ordnance. Soto and Acosta climbed above the two Salvadoran FG-1s, which had apparently not spotted them as they flew on toward Honduras. Soto dove on the Salvadorans, followed by Acosta, and hit the first one with his first burst of fire. It caught fire and the pilot bailed out as Soto's speed carried him past the second Corsair. Soto missed Acosta's call of two more enemy aircraft, and suddenly found himself with the second Salvadoran FG-1 on his tail and firing. For the next several moments, Soto put his F4U-5 through tight turns, dives and zoom-climbs in a downhill battle trying to shake the Salvadoran. Finally, he entered a split-ess, but pulled out halfway through. The Salvadoran pilot continued the maneuver, which allowed Soto to get on his tail. His first burst knocked off an aileron, and the second exploded the other Corsair - the pilot had neglected to depressurize his fuel system before entering combat. Soto pulled out to find himself flying past the still-parachuting pilot of his first victim. The dogfight had lasted only long enough for the first Salvadoran to descend 9,000 feet, though Soto later recalled "it was like a century."

Hostilities ended on July 19. Neither side lost any aircraft to triple-A, while Soto's three kills were the only ones made by a pilot of either air force.

Nine of the Honduran Corsairs were still operational in 1978, thirty-eight years after the first flight of the first Corsair. All but Soto's eventually came back to the United States in the early 1980s, where they nearly tripled the number of surviving Corsairs flown as warbirds. Today, Fernando Soto's F4U-5NL is the gate guardian at Tegucigalpa, and probably could not be restored to flight status due to exposure to the elements.

While I was fortunate with my first F4U-5N to obtain a kit that did not suffer from the "forward fuselage ridge" problem in a noticeable way, I was not so lucky with this kit. The problem is due to the fact that Hasegawa chose not to create a separate fuselage mold for the three different airplanes of the late Corsair series, but opted to have a separate mold of the forward fuselage which could be changed for the three different types. As a result, there is a mold "ridge" just ahead of the fuselage gas tank, which varies in severity. In the case of this kit, after I sanded down the ridge area, there was still a "wave" in the plastic, which could only be cured by use of putty there. If you have to fix this problem on your model, be sure to scribe the surface detail more deeply before you start sanding things down, which will give you a guide for re-scribing the area when you have gotten rid of the "ridge."

The Honduran Corsairs never received a repaint while they were in the country. However, photographs taken in 1978 show that while the Glossy Sea Blue paint had faded on the upper surfaces, it had held up to the tropical conditions surprisingly well. Thus, when I painted this model, I gave it an overall coat of Gunze-Sanyo "Midnight Blue" then went back over the upper surfaces with first a bit of Tamiya "Dark Grey" mixed into the original color, and then a bit of Tamiya "Blue," to give a subtle sun-fading effect on the upper surfaces of the wings, horizontal stabilizer, and upper areas of the fuselage. I also painted the "anti-glare" area ahead of the cockpit with Gunze-Sanyo "Navy Blue," a very good color for the "Non-Specular Sea Blue" used as anti-glare on these airplanes.

SuperScale released a very good sheet of Corsairs, 48-500, in 1995. This has Phil DeLong's VMA-312 F4U-4 Korean Yak-killer, Soto's Soccer Warrior, and a VMF(N)-513 Korean night fighter, which has the codes in the wrong color of red and the wrong size. The other two sets or markings are fine, and even include stenciling in Spanish for Soto's airplane. The decals went down with no problem under a light coat of Micro-Sol.

I painted mud smears on the prop blades and the lower wings aft of the main wheels and the inside of the tail wheel doors, since the Honduran airfields during this time were all muddy unimproved strips; I created the exhaust staining with Tamiya "Dark Sea Grey" oversprayed with Tamiya "Smoke", and some paint chipping on the leading edges of the wings and tail, and around the cowling and engine access panels. Past that, the major way to show weathering on an airplane painted Glossy Sea Blue is to flatten the color in those areas exposed to the sun, which I did with my "Flat Future" mixture of Future and Tamiya "Flat Base."

Fantastic build, Tom!

I wasn't aware of those historical notes and I went through them with great pleasure!

Nice Tom. I built 1/72 versions of both country's Corsairs - it's such a fascinating slice of history.

Nicely done Tom and some good history too. Thanks for sharing that.

Nice and interesting build!

Great achievement, Tom.

Thanks for sharing the hirstorical background.

A great looking Corsair! Thanks for the history lesson which is always a highlight for me!

Great model Tom & a good read as well (as always).