On This Day…March 21st

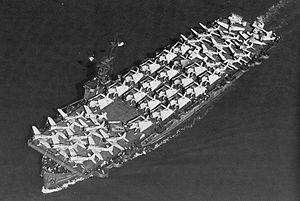

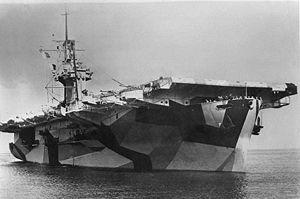

40mm Bofors gunnery drills aboard USS Makin Island (CVE-93) on 21st March 1945, in preparation for the Okinawa Campaign.

Of the eleven US carriers lost in World War II, five were Casablanca Class Escort Carriers like the Makin Island;

CVE-56 Liscombe Bay...

Sunk 24 November 1943. Submarine torpedo launched from IJN I-175 SW off Butaritari (Makin).

CVE-73 Gambier Bay...”

Sunk 25 October 1944. Concentrated surface gunfire from IJN Center Force during Battle of Samar.

CVE-63 St. Lo (ex-USS Midway)...

Sunk 25 October 1944. Kamikaze aerial attack during Battle of Leyte Gulf.

CVE-79 Ommaney Bay...

Sunk 4 January 1945. Kamikaze aerial attack in the Sulu Sea en route to Lingayen Gulf.

CVE-95 Bismarck Sea...

Sunk 21 February 1945. Kamikaze aerial attack off Iwo Jima.

German SdKfz. 7/2 half-track vehicle with light anti-aircraft gun in Russia, 21st March, 1944.

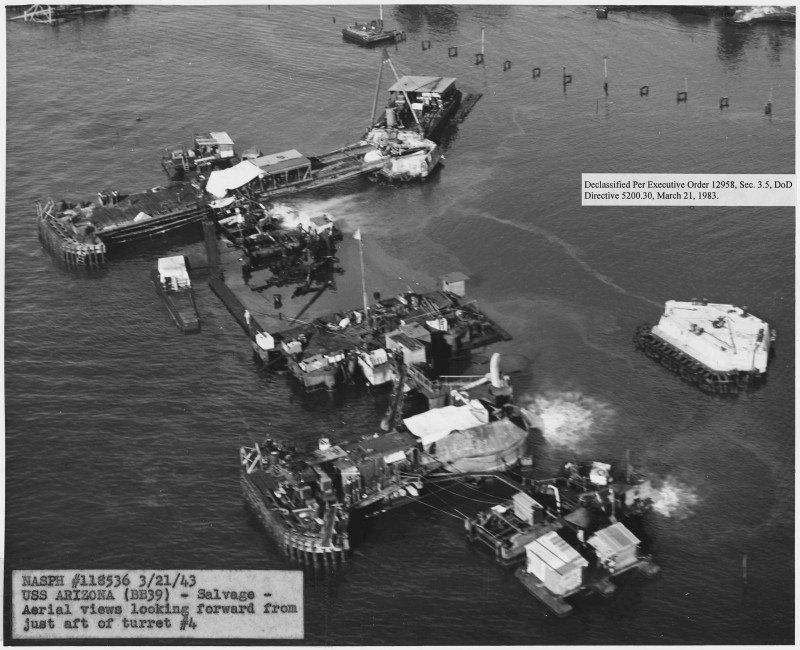

Ariel view of the continuing salvage work on the sunken battleship USS Arizona in Pearl Harbor, 21st March, 1943, a year and a half after the attack.

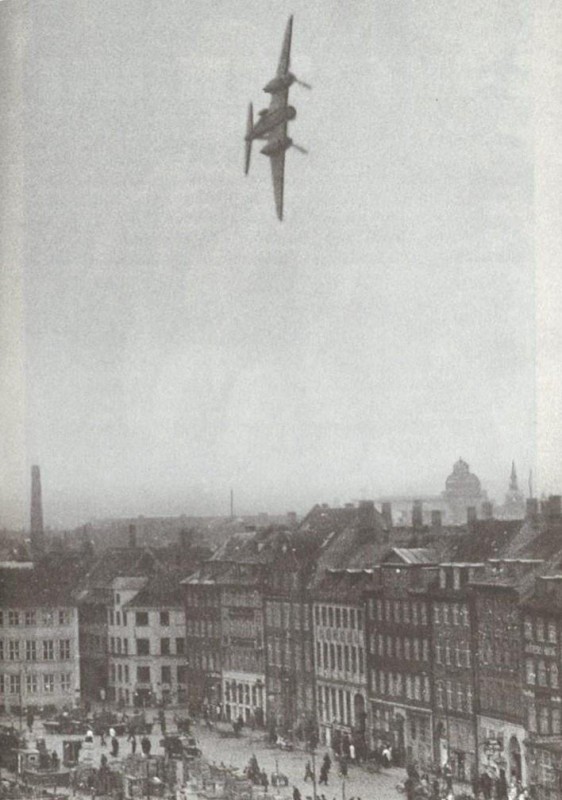

On the 21st March, 1945, twenty Mosquitos of the No. 2 light bomber group, escorted by thirty P-51 Mustangs from the 11th fighter group took off from RAF Fersfield in Norfolk as ‘Operation Carthage’, with the objective of bombing the Gestapo Headquarters, a huge U-shaped building in the center of Copenhagen known as the Shellhus (“Shell House”).

In a similar scenario to ‘Operation Jericho’ (the low level Mosquito bombing of Amiens prison in France), the British claimed to be working from local intelligence and pleas to free resistance prisoners. The British agreed to these requests after initial refusals based on the risks (rightly as it transpired) to civilian life.

The Mosquitos flew in low, reaching Copenhagen at 11:00am. What followed was was tragedy on a grand scale.

The bombers made their runs in three waves of six aircraft (two of the Mosquitos were reconnaissance planes filming the mission) while the Mustangs patrolled for Luftwaffe defences.

Because they were flying so low, however, one of the aircraft (SZ977, ‘T for Tommy’) of the first wave clipped a lamppost and crashed into local houses, with its bombs exploding near a local school, St Joan of Arc Catholic School.

While the remaining five Mosquitos of the first attack dropped their bombs on the prison, the incoming second and third waves were confused by the explosions caused by ‘T for Tommy’ and dropped their bombs by mistake on the school.

In a terrible reckoning of the costs of war, 133 Danish civilians died during or after the raid, including 86 within the school. Four Mosquitos and two Mustangs were lost, with nine aircrew killed.

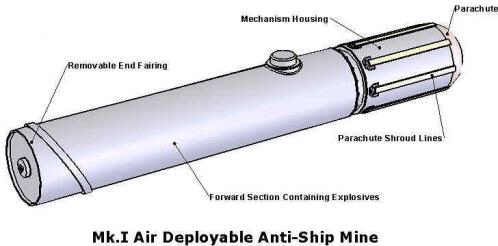

On Friday, March 21st 1941, two RAF Hampden bombers flew out on a mission to lay sea mines in the natural harbour of Brest, in France. The aircraft flew across the Channel and managed to avoid coastal AA fire, traversed the coast of France and were well on their way to deliver their load.

Before the dropping The mines, the bombadier had to remove two safety screws to activate the mine. Once dropped, the mines were slowed by a parachute to allow a gentle and vertical entry in the sea. They would then float, ready to explode when touching a ship.

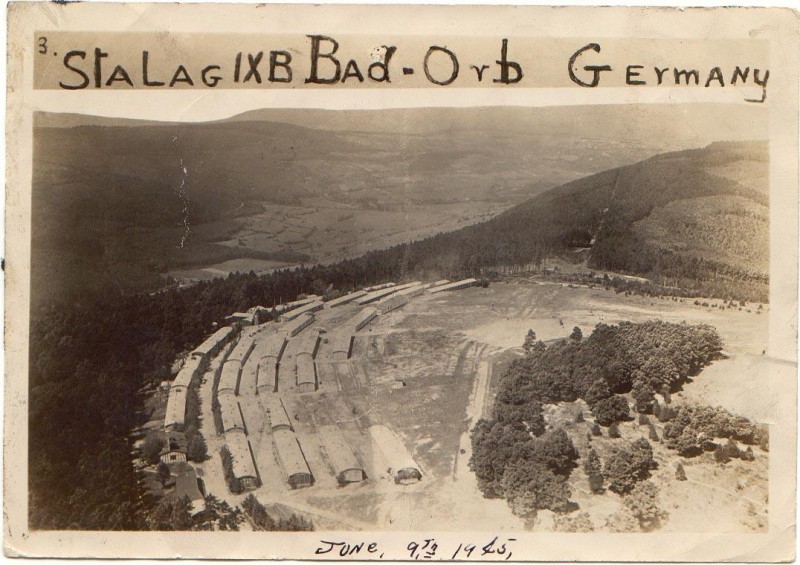

Given the fragility of their cargo, what happenened next was unbelievable. One of the Hampdens (X3132) was hit by a massive strike of lightning that tore apart the fuselage, dislodged the mine, and jettisoned it from the low flying plane. Weir Norman Stewart and Alexander William Millar, who were both 21, were killed instantly. Two other airmen were hurt, including the pilot, Oliver Barton James, whose’s left arm was seriously burned and injured. James was captured and treated as a PoW in a French hospital (and had his arm amputated) before being moved out for internment at a transit camp in Frankfurt, en route to Stalag IX.

On November 21st, James managed to escaped from this camp together with Sergeant William McGrath, also severely injured. The two fugitives, despite their handicaps, quickly arrived at Les Essarts in the suburb of Rouen, where they met the mayor who recommended them to reach a safe place at ‘Oiselles sur Seine’. On November 24th, 1941, they were welcomed there by French Freedom Fighters. The same day, they had to take the train to Paris where they found assistance and a safe housing.

Both men moved on to ‘Nevers’ where they remained 3 weeks and tried to cross the demarcation line. They finally crossed the line at night on a boat by crossing the Loire river, with the help of a guide. On the other side a car was waiting for them to drive them, always by night, towards a railway station in Chemin sur la Fosse. They arrived at Marseille railway station on December 22nd at 6 am in the morning where a woman was waiting for them.

On December 24th, sergeants Oliver Barton James and William Magrath left Marseille for Toulouse then Carcassonne. Then they took the direction of Perpignan where someone was waiting for them at the "Hotel d'Angleterre". There, a guide led them by walking, along the coast via Port Vendre and Banyuls, then towards the Spanish Border where they reached the railway station of Vilajuiga in Catalonia. They paid their guide the amount of 12, 000 francs each. Eventuallly they reached the British Consulate in Barcelona on December 29th, 1941. On March 4th, 1942, sergeants Oliver Barton James and William Magrath left Gibraltar aboard a boat and arrived in Great Britain at Gourock in Scotland on March 7th, 1942, almost a year after James’s Hamden had crashed. They were only the third and fourth men to have successfully escaped from German concentration camps.

Oliver James campaigned to return to flying after returninghome. After much haranguing, the hospital made him a special prosthetic arm and the RAF retrained him for fighter duty. On Sunday, October 4th, 1943, James was attacking targets in Northern France when he was shot down and killed in his Typhoon (JP434) by Siegfried Lemke in a FW 190 of JG2. He was still only 23 years old.

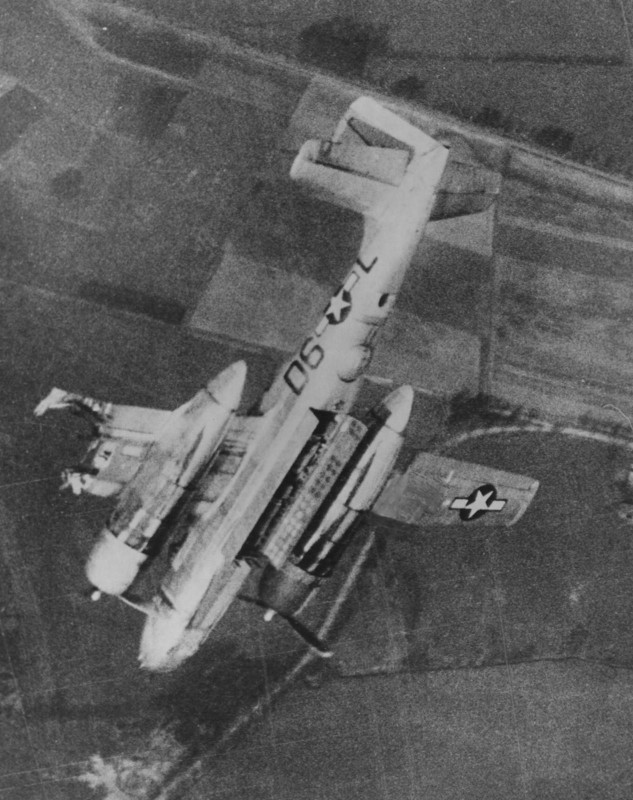

642nd Bomb Squadron, 409th Bomb Group, 9th Air Force...

This Douglas A-26 Invader lost on the 21st March,1945 on a mission to Dulmen, Germany. She took a direct hit by flak at 11:03am, about 2 minutes from bombs away and went straight down, crashing near Velen, Germany. No chutes were seen. 642nd Bomb Squadron, 409th Bomb Group, 9th Air Force

Lost on the 21 March 1945 mission to Dulmen, Germany. Took a direct hit by flak at 11:03am, about 2 minutes from bombs away (you can see bomb bay doors open) and went straight down, crashing near Velen, Germany. No chutes were seen.

David, what a couple of great stories. It’s hard to conceive an aircraft being “sliced” by lightning, even then the electricity discharge wires were surely used, albeit with a primitive technology compared to our day and age, and the planes were surely aluminium made (entirely or partially at least). What could explain that catastrophic event with Hampden in your opinion?

Hi Pedro. I I’d a little research into this after reading this this story. My rudimentary knowledge extends as far as knowing modern aircraft act as a very efficient ‘farraday’ cages, and the last commercial aircraft brought down by lightning was in 1967. However, an eye witness and pilot report very much confirmed the lightning seemed to cause the crash, probably some structural weakness regarding the fuel tank.

The amazing thing (or maybe not, my knowledge in these things is poor) is that the mine (all one ton of it) didn’t detonate either in the initial explosion or when it hit the ground.

Yeah, that part of the story is also astonishing

David,

I read your entries every day and enjoy what I learn from them. It has motivated me to recommend the thread to a couple of friends that would not necessarily be active modelers. One of those friends was a modeler, but at ninty-three he is no longer in the active category. In his active Air Force days he flew the B-26 (Douglas) B-47 and B-57. I am eager to hear if he as checked into iModeler for a look.

Thanks, Russell, I appreciate you spreading the word. My hope is that some of the articles might inspire a build or two on iModeler, so your post really struck a chord.

The support, as always, means a lot.