On This Day...February 26th

There's no substitute for experience. On 26th February, 2012 the North American P-51 known as ‘The Brat III' (owned and operated at considerable expense by the Cavanaugh Flight Museum in Dallas) found itself circling above Mobile, Alabama with the port main landing gear of the vintage P-51 stuck halfway down. Faced with a potentially ruinous crash landing, pilot Chuck Gardner (with paying passenger in the seat behind him) calmly worked the operating procedures with no effect.

Gardner started a conversation with a fellow pilot on the radio, who relayed messages to and from Doug Jeanes, the director of the Cavanaugh Flight Museum, who answered the call for help in Dallas, Texas. The museum was touring ‘The Bratt III', a World War II combat veteran, across the country, having owned the vintage P-51 for more than 20 years, including the eight years spent restoring her.

After picking the brains of various pilots, and with the Mustang continuing to circle the aerodrome, it occurred to Jeanes that veteran and test pilot Bob Hoover (cited in previous On This Day... article) whose venerable career included countless flights in a P-51, might have an idea or two.

Hoover often found himself attending and flying in many air shows where airplanes got into trouble (these are old aircraft and pretty temperamental) and he'd offer to form up on the wing and talk the pilot through it.

“Somebody would have a problem almost every other race, and over the years I must have talked down 30 or 40 airplanes that were in real trouble,” Hoover said in a telephone interview. “As a test pilot, I had more experience, probably, than most people.”

Hoover also had experience with a very similar problem—twice over. First in World War II, and later at the Transpo '72 airshow at Washington Dulles International Airport, Hoover had to land a Mustang on one wheel, which he evolved into a part of his show (see below). In 1972. Hoover explained the up lock sometimes failed to release and there was no hope of extending both wheels. He put the old warbird down on one leg, walking away uninjured, but the aircraft required extensive repair following the inevitable prop strike.

On Feb. 26, Hoover said the main wheel was not locked inside the fuselage, so he encouraged Gardner to keep trying various troubleshooting manoeuvres: an abrupt pull-up that could dislodge the gear with G forces, and a hard yaw to bring the force of the slipstream to bear on the stuck gear assembly.

“Boot enough rudder there at landing gear down speeds, get a side load on it, it would force it out and into the locked position,” Hoover said. “I've been there, I've done that a couple of times.”

Jeanes, on the phone from Dallas to Hoover in Los Angeles, encouraged Gardner to keep trying the maneuvers over Mobile Bay. “Just slip it, skid it, yaw it, whatever you have to do to get some air under the door.”

After about an hour of maneuvering, the landing gear at last dropped into the down and locked position, and a smooth landing followed.

The problem was diagnosed as a bad valve which controls the pressure in the shock and strut assembly, preventing the strut from fully extending and luckily the Mustang had departed with plenty of fuel on board.

Hoover said he was happy to lend his experience to a pilot in a pinch—again.

“I was so pleased we could save the airplane, or that I … had anything to do with it,” Hoover said.

Experience...(a touch of genius also helps).

USAAF B-24D-53-CO Liberator, ‘Beautiful Betsy', of the 528th Bomb Squadron of the 380th Bomb Group went missing in Australia on 26th of February 1945 with the loss of 8 lives (6 American and 2 British service personnel). The Liberator was on a ‘Fat Cat' mission from Fenton (Northen Territories) to Eagle Farm airfield in Queensland. Fat Cat missions were ‘unofficial' runs where a crew would gather ‘taxes' from the squadron and pick up goods (food, drink usually) from civilian sites.

The wreckage of ‘Beautiful Betsy' was not discovered until almost fifty years later on 2 August 1994, when park ranger, Mark Roe, was checking the results of a controlled burn-off in a local National Park, about 80kms from Gladstone. Standing on an escarpment, he saw something glinting in the sunlight about 800 metres north of his location. On investigation he found the wreckage of the B-24 which had crashed on the side of a remote hillside.

M30 ammunition carrier of 557th AFA Battalion moves over a treadway bridge outside Linnich, Western Germany, on 26th February 1945.

An atmospheric shot of the USS Lexington (CV-2) sailing through aircraft-deployed smoke screen, off Panama, 26th February, 1929.

German Tiger I on a road in Tunisia, 26th February, 1943.

Anti-submarine Leigh Light installed beneath the wing of a Liberator bomber of the RAF Coastal Command, February 26th,1944. ‘Leigh' lights were powerful (22 million candela) carbon arc searchlights of 24 inches diameter that fitted to a number of the British Royal Air Force's Coastal Command patrol bombers to help them spot surfaced German U-boats at night.

A sailor sits (if you look closely enough) in the starboard steering gear room of the USS Intrepid, viewed through a torpedo hole in the hull 15 feet below the waterline. The damage was caused by a torpedo bomber hit during ‘Operation Hailstone' raids at Truk. This photo was taken as the water receded in Pearl Harbor Drydock number one, 26th February 1944.

FR-1 Fireball fighter at rest at Moffet Field, California, United States, 26 Feb 1945.

On February 26, 1935, German nationalist leader Adolf Hitler defied the terms of the Treaty of Versailles and ordered the reestablishment of the German Air Force, to be known as known as the ‘Luftwaffe'. The leadership disguised pilot training as lessons to fly gliders, something allowed by the treaty. As German industry developed war planes, the deceit that the aircraft were civilian planes was used as a cover story, while German pilots gained experience of combat flying in the Condor Legion of ‘volunteers' during the Spanish Civil War. The rest, as they say, is history.

The following narrative is culled from interviews, recollections, and medical reports.

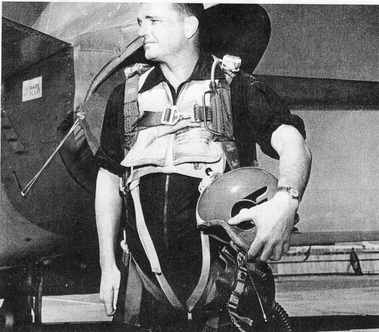

On the morning of Saturday, 26 February 1955, North American Aviation (NAA) test pilot George F. Smith dropped by the company plant at Los Angeles International Airport to submit some test reports. As he returned to his car, he was hailed by the company dispatcher. A brand-new F-100A Super Sabre needed to be test flown prior to its delivery to the Air Force. George was asked if he'd mind doing the honors?

Smith quickly donned a company flight suit over his street clothes and pre-flighted the F-100A Super Sabre (S/N 53-1659). After strapping into the big jet, Smith went through operational sequence of aircraft flight control and system checks.

Smith executed a full afterburner take-off and the Super Sabre took to the air. Accelerating and climbing, the aircraft was almost supersonic as it passed through 35,000 feet. Peaking out around 37,000 feet, Smith sensed a heaviness in the flight control column and knew that something wasn't quite right.

The F-100 became completely unresponsive and ignored all Smith's control inputs. Instead, it continued an uncommanded dive. While shallow at first, the dive steepened even as the 215-lb pilot pulled back on the stick with all of his might. The Sabre's hydraulic system had failed and as the aircraft accelerated toward the ground, Smith rightly concluded that the plane was a gonner, the only option open to him was to bail. However, he also knew that the chances were small he'd survive, knowing that no-one has ejected and lived at the speed he was now travelling.

He jettisoned his canopy and the roar from the airstream around him was “unlike anything (he) had ever heard”. Almost patalysed with fear, George pulled the ejection seat trigger.

His last recollection of this flight was that the Mach Meter read 1.05 - which is 777 mph at the ejection altitude of 6,500 feet. Apparently, flight conditions corresponded to a dynamic pressure of 1,240 pounds per square foot: as he was exploded from the cockpit and into the airstream, Smith was subjected to a drag force of around 8,000 lbs producing on the order of 40-g's of deceleration.

Mercifully, there was no recollection of what came next. The ferocious windblast stripped him of his helmet, oxygen mask, footwear, flight gloves, wrist watch and even his RING. Medical tests, scans, diagnostic make ups, and simulations tell us blood was forced into his head which became grotesquely swollen and his facial features unrecognizable. His eyelids fluttered and his eyes were tortuously mauled by the aerodynamic and inertial load of his ejection. Smith's internal organs, most especially his liver, were severely damaged. His body was severely bruised all over and beaten as it flailed end-over-over end uncontrollably.

Smith and his seat parted company as procedures dictated and automatic deployment of his parachute engaged. The opening forces were so high that a third of the parachute material was ripped away. but unbelievably the unconscious pilot landed about 75 yards away from a fishing vessel about a half-mile form shore. Again, quite unbelievably, the boat's owner was a former Navy rescue expert. Within a minute of hitting the water, Smith was rescued and brought onboard.

George Smith was very near death when he arrived at the hospital. In severe shock and with only a faint pulse, doctors went to work on him but it was to be six days before George regained consciousness. Even then, he could hear, but was completely blind. His eyes had sustained multiple subconjunctival hemorrhages and the prevailing thought at the time was that he would never see again.

Eventually, though, George did recover almost fully from the world's first supersonic ejection. He spent seven months in the hospital and had to undertake several crucial and dangerous operations. During that time, Smith's weight dropped to 150 lbs, was left with a permanently damaged liver, but his vision returned to normal.

Amazingly, he also got back in the cockpit.

First, he was cleared to fly low slow prop-driven trainers. Ultimately, he got back into jets, including once more his nemesis, the F-100A Super Sabre.

George Smith was thirty-one years old at the time of his supersonic expulsion, and lived a happy and productive thirty-nine more years afterwards.

Interesting coincidence - just this weekend, I purchased myself (on behalf of my wife, for my birthday gift), a consignment 1/72 MPM kit of the Ryan Fireball. Although I've always considered the Fireball a dumpy and uninteresting subject, the box art scheme really drew me in (and since I didn't have one in my stash, I could justify it with the wife!).

1 attached image. Click to enlarge.

It's actually not "dumpy and uninteresting." I once talked to a former USN pilot who was in the one squadron that went operational with the FR-1 out at Chino (where the only FR-1 capable of flight is being restored to fly - prop only). He told me it was the most maneuverable airplane he ever flew, that he could fly rings around an F8F. "We'd have flown them into the ground," regarding possible combat over Japan. His favorite thing to do was to shut down the piston engine and feather the prop, and fly past other military aircraft on jet power alone, and then execute a climb "with no engine." The one big problem was the nose strut wasn't really strong enough for repeated carrier ops.

Hi Greg. If anyone can make her lithe and elegant, 'wheels up' and on a nice stand, you can, Greg.

"on behalf of my wife..." bet that strikes a chard with a few out there.

What a GREAT piece you presented us today, David! Mr. Smith's episode is amazing!

PLUS ... Bob Hoover has been one of my heroes for decades. Sadly, the only time I've seen his exhibition was on You Tube ... never in person. He was a VERY "classy" guy and I've never heard anything bad about him. A TRUE hero!

Bob was a "scamp" outside business hours, trust me. A typical flying hot shot. I used to watch his routine up at Reno - every flight exactly the same as the others. Once another photographer complained that he was "boring." "He always does the same thing the same way." To which those of us who were pilots replied, "That's hard to do!"

George Smith was once out at Chino back in the early 80s. A very unassuming kind of guy; unless you knew what he had done you'd never know it from him.

Thanks, Jeff. All of those test pilots had the ‘hero gene’ by the bucket load. I don’t know what the mortality rate was but I’m pretty sure it wasn’t worth what they were paid.

So true David, but I wonder if the vast majority of them did it mostly for the thrill, the aura and the reputation, and not necessarily the money. Whatever the reasons I’m glad they did, because look where we are today as a result of their “hero genes.”

I noticed the old airship mooring beyond the port elevator on the FR-1. Something that had been long removed by the time I was stationed at Moffett.

Another great post.

Affectionately known as "Chuckstang" 🙂 Chuck is a great stick...he checked me out in the T-6 when I started at Warbird Adventures. He spent almost 6 months on the road with us flying Betty Jane right after we got her going.

Chuck flying off my wing somewhere near Winterhaven in 2011.

1 attached image. Click to enlarge.

Now this is really cool too !

Wow, David, this post represents a LOT of work. You're a servant to us all in these posts!

I was fortunate to see Bob Hoover fly his yellow "Rockwell" Mustang several times at different airshows many years ago. I remember seeing him do the landing with one leg up but never knew the stories behind how it came about... He was a very gifted pilot... sensational is a word that comes to mind. He did the exact same thing every time... and like mentioned above, it has to be very hard to do.

Another excellent posting David...

Thank you.